Station 119

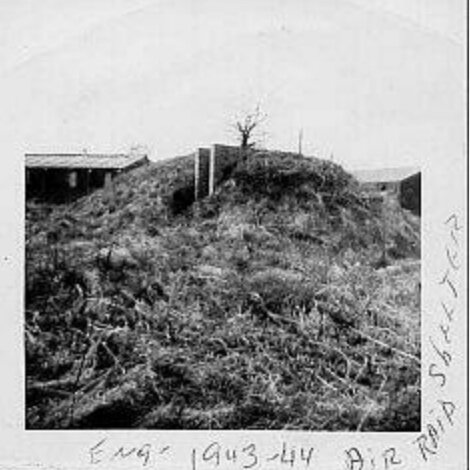

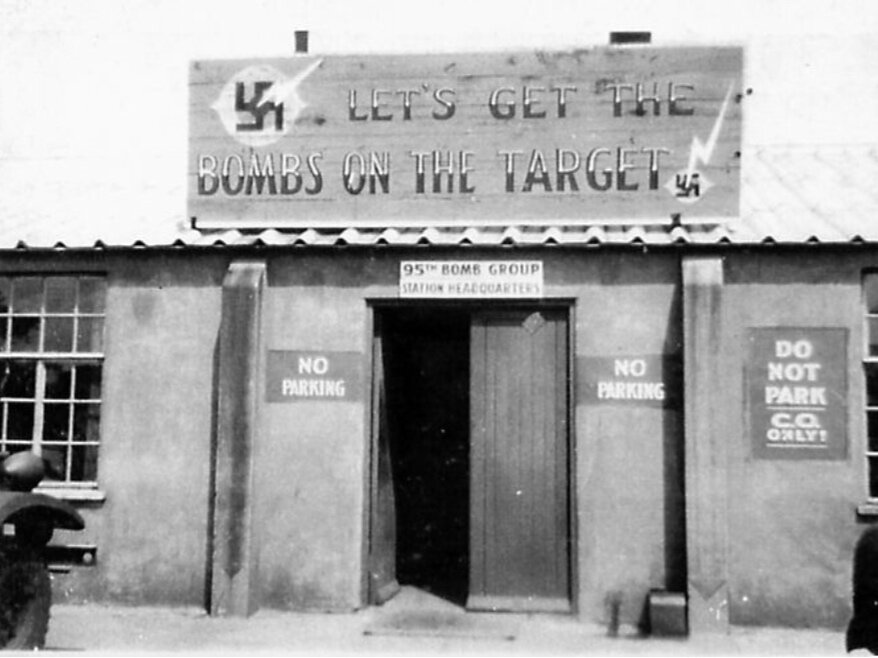

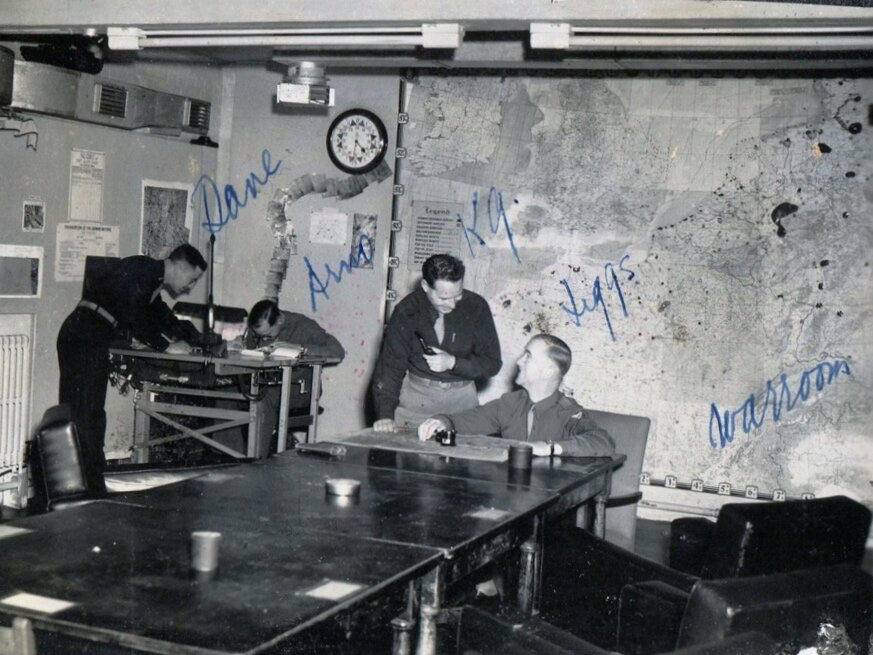

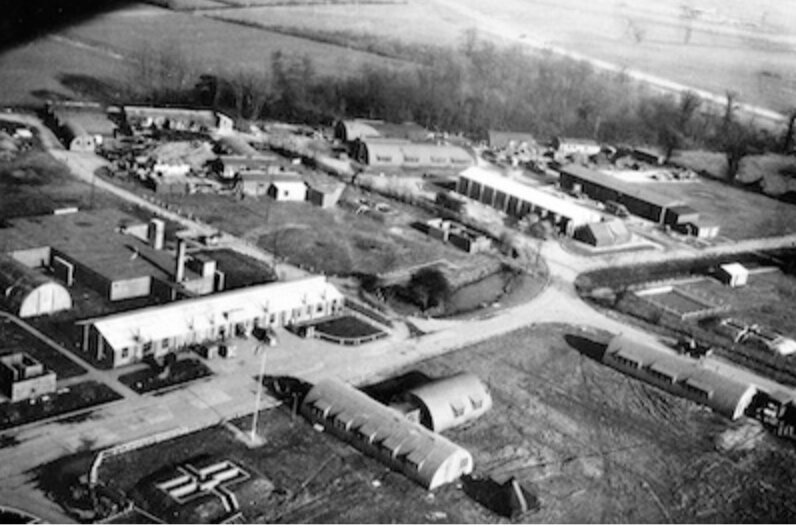

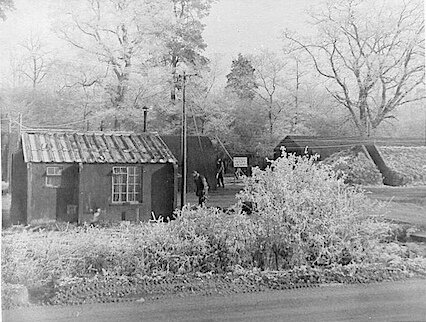

The 95th BG arrived in England in the spring of 1943. After short stays at Alconbury and Framlingham, the Group moved to Horham Airfield, Station 119, on June 15th, remaining there for the duration of the War. Planned originally for RAF use, the Horham airfield was provided to the U. S. Army Air Force in 1942, and construction commenced—two hangars, station headquarters, administrative buildings, and living sites. The sprawling base spanned four parishes: Horham, Denham, Redlingfield, and Hoxne. In September 1943, Horham was also designated as headquarters for the 13th Combat Bombardment Wing of the 3rd Air Division.

By 1943, there were more than 100,000 U. S. airmen based in England, mostly in East Anglia. In an area smaller than the state of Connecticut, there were more than 100 RAF and USAAF bases. The fields and wooded areas of the counties of Norfolk, Cambridgeshire, and Suffolk became speckled with hastily built bases—on which many locals worked daily. As many as 400 civilians worked on the Horham base alone.

The arrival of so many Yanks was termed “the friendly invasion,” with more servicemen on the Horham base than people in the surrounding villages and towns. To a Britain used to austerity after years of war, the Americans arrived with exotic goods—Coca Cola, peanut butter, chewing gum, and Glenn Miller. Many local women did washing for servicemen, and villagers got used to seeing the Flying Fortresses setting off on missions in the morning as children were going to school. Bonds grew between the Yanks and the locals. The American servicemen were especially generous to the children, no doubt missing their own younger siblings or children.

Despite having food and drink that was the envy of the rationed locals, the men of the 95th lived mainly in metal Nissen huts through tough English winters, with only small pot-bellied stoves to keep them warm. It is no wonder that they found sanctuary and solace in the bars on base and in the surrounding area.

On base, many rode bicycles to cover the vast area of the station. Ground personnel, who remained for the duration of the War, were tight with the locals, but learned to their sorrow not to make strong attachments to the flight crews, having watched for too many planes that didn’t come home. Similarly, flight crews were close-knit, but might not spend much time with other crews or ground personnel.

Once in London, the men, many of whom had never been in a city of that size in their lives, soaked up the local sights – even in bombed-out, blacked-out London. They made it to all the places they had read about back home: Picadilly Circus, Buckingham Palace, the Tower of London, and more. Some of the men shopped for special gifts for mothers, sisters, wives, and sweethearts. Others found their brides in the U. K.

The base at Horham was de-activated in August of 1945 – just over two years after having been established. This period of intense activity in Suffolk had forever changed the lives of thousands of U. S. servicemen, their families, and the locals.

Maps of the Airfield

From the collection 334th pilot Bob Cozens, courtesy of Tom and Peggy Cozens